Category: Travel

Waited 5 years for this Grand Canyon trip

You should take a rafting trip through the Grand Canyon with an outfitting company that sends along a string quartet, a fellow U.S. Census worker told me in 2010. That went on the to-do list immediately, but it took several years for the trip to actually happen.

First, we had to find time for it. Kathy retired in 2014. I retired, went back to work, retired again, work again, retire again and so on until 2022. But during my 2018 retirement, we thought we had time for the Grand Canyon trip. We called Canyon Explorations/Expeditions in Flagstaff, AZ, and they said they’d put us on the waiting list.

So we got on the list. No go in 2018. Not in 2019. And then COVID came around in 2020 and 2021. No go those years.

But it was on for August 16, 2022, with four friends from Montana, until I came down with COVID the week before. I spread the disease to six other family members, including Kathy, within a week. No one wanted us on a 15-day rafting trip, and I was too addled to paddle. The Montana friends went, and Canyon Explorations/Expeditions found us a spot in 2023.

And we went. I loved every minute of it, even getting dumped out of the paddle boat in the Horn Creek Rapids. Kathy does not like sleeping on the ground but braved the rapids, a rattlesnake she discovered on the way to the “Groover” (the ammunition box with a toilet seat that served as the carry-away poop spot) and bugs, scorpions and my snoring.

The guides were informative, helpful and cheerful. The food they cooked was hearty and tasty. And the string quartet . . . outstanding. Led by Steve Bryant, who plays violin in the Seattle Symphony, the quartet played for us in side canyons, and once, even as we floated down the river, our rafts tied together.

Now, we are back in Seattle, thinking about what the next trip will be.

And attending Seattle Symphony concerts.

A manga museum could save us from A.I.

Wandering back to our hotel from a countertop ramen shop in Kyoto, we came across a sign that read, “Kyoto International Manga Museum.” Finding it serendipitously surprised us since we had told the tour group arranging our trip that manga and anime topped the list of what our grandson wanted to explore in Japan. Suggestions on what to do with our free time in Kyoto mostly involved geishas, kabuki and cherry trees (not in bloom).

We followed the sign into the museum, and then manga became my top attraction in Japan. The one and most important activity in the museum is reading. On the day we were there, the museum had guest speakers talking about manga as a cultural phenomenon, but mostly visitors were there to read some of the more than 300,000 volumes of manga, which are ways of telling stories through drawings and words: graphic novels, or, some would say, comic books.

What better place to hold a museum dedicated to reading than a former elementary school. The Tatsuike Primary School opened on November 1, 1869, after the nation’s capital was moved from Kyoto to Tokyo. That brought about the threat of economic decline, but the citizens of Kyoto turned to education to stave off a downfall. The citizens around the Tatsuike school raised money to build it, taking no money from the Kyoto government.

In recent years, as people moved out of the city’s center, the student population fell from 800 in the 1950s and 1960s to 110 in 1994. Five schools were consolidated into one school in 1995, leaving the Tatsuike building vacant.

However, the school is in the central part of the city, the building is attractive and has a rich history and tradition. So, the school was converted into the Kyoto International Manga Museum “intended to serve as a new center for promoting lifelong learning through maximum use of the Museum’s functions as both a museum and library. The Museum is also expected to become a new sightseeing spot where people gather to enjoy the richness of manga culture.”

How best to tell the story of the school? Through manga, of course. Those volumes are in the museum.

At one time, manga “was misunderstood as harmful, and, at another was something people were ridiculed and thought to be stupid for reading,” says a sign introducing Aramata Hiroshi, the executive director of the museum. “But we have left those days behind us, as manga has begun to be valued as one of the coolest cultural media.”

Hiroshi, 76, worked as an assistant editor for an encyclopedia while writing an award-winning novel, “Teito Monogatatari” (Tale of the Imperial Capital). As a writer and translator, he has produced 350 books and once sought to become a manga artist. He says he has been reading manga for more than 60 years.

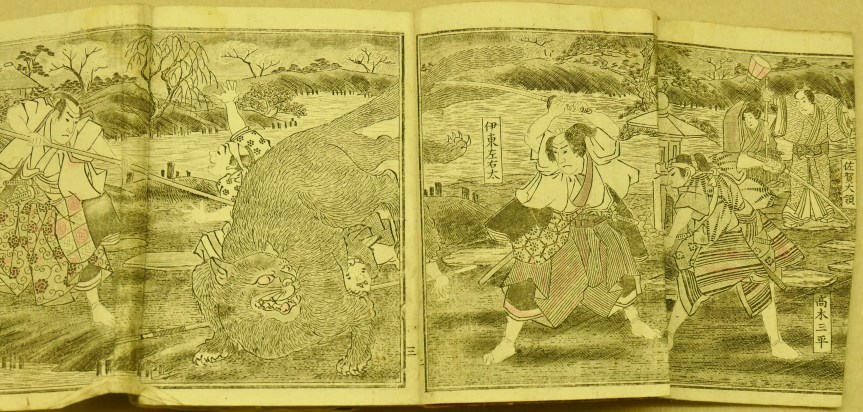

One guide on our trip told us that manga dates back more than a thousand years, starting with a story about a rabbit and a frog fighting each other. The unlikely winner was the frog. But he was a sumo frog. Anyone fact-checking that tale would probably find more Pinocchios than in a Trump campaign speech. This history of manga is probably more reliable.

The museum does include a few ancient drawings, but the goal of the museum is to preserve modern manga, which is still being produced in reams and reams of paper.

“This museum handles printed items (mostly magazines and books of manga) that were published from the modern age. . . . manga magazines have shaped the diversity of Japanese comics and manga is not only about stories, but also conveys knowledge and makes complicated information easily accessible thanks to their expressive devices.”

The museum’s “Hall of Fame” dates from 1912, and what is there is for people to read.

Given my love of comics (see https://madcapschemes.com/2023/03/11/as-papers-kill-comics-a-museum-is-saving-them/), finding another museum devoted to them filled my suitcases and emptied my wallet. Manga covers everything from children’s stories, adventure tales, science fiction, fantasy and non-fiction topics such as history.

History.

Told in comics.

My cup of oolong tea.

I purchased three volumes on the history of Japan from 1926 to 1989 and ordered the fourth and final volume when I got home.

“Showa: A History of Japan” refers to the era when the late Emperor Hirohito reigned, from 1926 to 1989. The author, Shigeru Mizuki (1922 – 2015) lived through that era. In the earliest days of Showa, the nationalism, militarism and extreme worship of the emperor, led to bad things for Mizuki, Japan and the world. Mizuki spent World War II on New Britain Island, now part of Papua New Guinea, where an artillery barrage took off his arm. He was not a good soldier and fell victim to the beatings common in disciplining the Japanese armed forces.

He grew up in poverty, starved during the war and returned to poverty after Japan’s defeat. The wars (World War II and the Second Japanese-Sino War from 1937 to the end of WW II) left few yens for most Japanese. But war also had a part in spreading wealth across Japan as their country was the center of resupply for both the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Those U.S. dollars helped Japan rebuild after the devastation from WW II.

Mizuki tells the Showa story in three ways: using old photos printed in stark black and white to tell the general history of international events and how Japan fit into them. He draws his own life story in cartoons and uses another of his manga creations to narrate. Nezumi Otoko (“Rat Man”) is there to introduce important personalities in Japanese politics, identifying who were the Japanese commanders in WW II battles (amazing how many committed suicide when their country was defeated – or were hanged by the Allies) and explaining the restrictive laws enforced before the war, such as the Public Security Preservation Law of 1925, under which anyone “altering the national identity” could be imprisoned (sounds like a model for DeSantis legislation). Nezumi Otoko is part of yokai, or Japanese supernatural beings such as ghost, goblins and monsters. Mizuki used them extensively in his manga, and besides, Morgan Freeman can’t narrate everything. Lots of footnotes also help.

In a recent column, Maureen Dowd bemoaned the dwindling enrollment in humanities as students fled history, art, philosophy, sociology and English into the fields of tech and science.

“I find the deterioration of our language and reading skills too depressing,” she wrote. “It is a loss that will affect the level of intelligence in all American activities.”

With artificial intelligence about to let loose with all kinds of things in every activity, Dowd wonders if we will be able to deal with it “unless we cultivate and educate the non-artificial intelligence that we already possess.”

Manga might not restore the level of Americans intelligence, but it’s better than “the kinetic world of . . . phones, lured by wacky videos and filtered FOMO photos . . . flippant, shorthand tweets and texts.”

There’re words on those manga pages. Best to have a museum dedicated to reading, first manga and eventually on to “slowly unspooling novels” such as “Middlemarch” and “Ulysses.” I’m one for two on that front. One more Showa book and then, maybe, I’ll try again to meet “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan” and the rest of the Irish gang. Maybe.

Not back to Egypt yet, but here’s a good read

I’ve got at least one more post on Japan that I want to get up on this blog before I return to our trip to Egypt. But here is a very good read from a blog I follow. John Wreford raises some of the same issues on water, the Nile and Egypt that I have made. But he is on a cycle, visiting farmers and quoting Herodotus.

Now, Japan: Back to Egypt soon

March and April in Egypt and then May and June in Japan. 2023 was not meant to be this way, but COVID is to blame — and will be blamed for another trip in September. So I interrupt what I wanted to say about Egypt and Ramses II with a little bit about our trip to Japan with a grandson (his high-school graduation present three years late).

Of the 130 million people living in Japan, 33 million of them live in the Tokyo area, which makes for some crowded streets. What it does not mean are litter, graffiti and people living on the streets — or at least not to what we saw in our two weeks visiting Japan. We did not look under every freeway pass or in every park where the unhoused people live in Seattle, but we only saw one or two people sleeping on the pavement.

Trash? Concentrated hunt for it. Two smashed beverage cans on day 1 during our eight-mile walk through the city. Day 2: Candy wrappers here and there occasionally but a spotty coverage at best. And there are very few trash cans on the streets. What do people do with their litter? Take it home with them?

But the most remarkable thing I saw on the streets of Tokyo — besides the rivers of people — were bicycles without locks. That can’t be in a big city like this, I thought. A closer inspection showed that yes, there were bikes unlocked, but many had a small ring locked around the back tire. Try to hop on and ride away? You’d be straddling the crossbar in seconds, and it would serve you right. No cycle stands to clog up the sidewalks. Bikes pulled off to the side with only a tiny ring to stop the bike thieves in Japan. Would that work in Seattle, in the United States of America? Hell no. Thieves here would drive around in a semi loading bike after bike until they spilled out the top as the truck drove to the hidden chop shop (once the former Seattle Times building) to cut through the tiny rings, leaving the former owner to buy another bike.

Back to Egypt: Anna has the complete record

If you want the complete story of our trip to Egypt, you should read this. Anna is a better note-taker, an accurate writer and a wonderful traveling companion (as is Ian, her traveling companion).

Not as a criticism but a suggestion, Anna really should be writing a traveling blog with all of her internet information linked so readers can find them more easily. But in the meantime, here are links to some of the sites Anna has included in her PDF, which is below:

From Anna: “Watch the YouTube videos on the Rescue of Abu Simbel and be amazed”. I liked this one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=83BZIzsyFPY

The Theban Mapping Project, which is excellent.

From Anna: “See YouTube videos on Dr. Weeks, including one done by the BBC”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11j2N2SAUiQ

I while have your attention (I hope), I would like to direct you to a podcast brought to my attention by Will. It is from the BBC series “You’re Dead to Me”, which promotes learning history “with comedy and without the crippling student debt”: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p09tvhv8

Here is Anna’s report on our trip to Egypt (use the bar on the right to see all pages):

Blogus interruptus: A bike ride across Arkansas

We interrupt my travelogue through Egypt for a bike trip across the state of Arkansas.

Why Arkansas? Because my sister has ridden across all the lower 48 states except two: Arkansas and Utah. Now she is down to one: Utah, where I have promised to be the Supplies And Gear (SAG) person because I cannot keep up with her.

There, I have said it. No more sibling rivalry. I have surrendered. I will forever be a half mile behind her — or more.

We started this ride in Fort Smith, Arkansas, right on the Oklahoma border and the Arkansas River, headed to the Mississippi River and Memphis, some 300 miles away by Mary Jo’s route.

Day One: The weather was chilly but clear. My new electric-assisted bike was working fine. It was Sunday morning, and the traffic was light. And for once in my rides with my sister, I cannot be blamed for cutting short the day’s ride. That blame goes to a nail that found itself lodged in Mary Jo’s tire somewhere near Midway, AR. We were 54 miles into a 77-mile ride when Mary Jo stopped, walked up to me and announced she had a flat tire. “Front or rear?” Rear. Ugh.

We decided to call the SAG team, otherwise known as our spouses. MJ spouse Don arrived for the rescue, and after a Mexican lunch at our first overnight stop in the town of Dardanelle, three of us spent more than an hour changing the tire.

If it hadn’t been for that nail, I might have shortened the ride. Somewhere in those 54 miles, I discovered that the auxiliary battery I bought to make sure I could make the average of 80 miles a day was not charged. So soon after those 54 miles, my bike would have been without power, and it would have been up to my two legs alone to get us to Dardanelle. The SAG team does not answer the phone on those calls.

After the tire repair, I examined my batteries, found the right slots for the charging tabs to go into and set them up for overnight.

Day Two: We rode 20 miles on a foggy morning before stopping for breakfast at the Mather Lodge in Petit Jean State Park. I’d go back to Arkansas just to stay at the lodge. The website says that the “native log and stone facilities (were) constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) beginning in 1933. The CCC built trails, roads, bridges, cabins, and the focal point of the park, historic Mather Lodge, a 24-room lodge overlooking Cedar Creek Canyon with a restaurant, meeting rooms, and gift shop.”

The story behind why the park is called Petit Jean is a charming — but sad — one. I hope you can enlarge and read it on the menu page I photographed.

Concerned about whether my bike and batteries would last the 90 miles for the day, I did lots of coasting to reserve battery power. Coasting downhill is the only time I can get ahead of my sister, who holds back on the descending grades. So somewhere on Arkansas Route 300, I got way ahead of her, so far ahead that I missed a turn. At the bottom of the hill, Mary Jo told me I had missed it and we had to ride back a mile, adding two miles to the day’s ride. Maybe because of coasting or maybe because the batteries have more juice than I thought, I made the 90-mile ride to Little Rock with power to spare. And I was feeling pretty good about staying less than a half mile behind my sister, until after dinner when she acknowledged that her electric-assisted bike had run out of power. At what point in the ride? About 75 miles, which means that she rode the last 15 miles on her own power. The ego balloon popped.

Day Three: I was slow. I do not like riding in the rain, which started before we got outside the city limits of Little Rock. It rained until we arrived at England, AR, 37 miles into the ride. The only good thing I can say is that Mary Jo’s route had us on beautiful roads: Hardly any traffic, smooth pavements, trees along the route. Besides being a great bike rider, my sister is also a pretty good navigator. She has to stop along the way to dig out her reading glasses to study her Garmin, her written route in a rain-proof folder and check her cell phone if there is coverage. Even when I think she has led us astray, I follow. We turn onto a road that says “No Outlet,” I’m riding behind her (a half mile back). “Road closed”? Who cares? There will be a trail at the end of it. Or a way through a construction zone, as happened in the photo below. “Sometimes it works, sometimes not,” Mary Jo said. “This time, it worked.”

I also do not like riding in the wind, which I thought came up after the rain even though my sister said, “This is not too bad.” So I was slow. So slow that at 64 miles, we called in the SAG team 13 miles short, realizing that getting to Clarendon, AR, before dark could be a problem.

In my defense, I would like to point out that walking 1.8 miles across the heaped-stone gravel “shortcut,” did not help our time. Still some work to do on navigation, sis.

Day four: It rained all night and into the morning. Rained hard. Enough that we walked to breakfast and decided to drive with the SAG team to Marianna, AR, ahead of the rain.

We kept dry for 60 miles into Memphis, TN, but were disappointed in the Mississippi River Levee because you can’t see the river from on top of the embankment, which is covered with crumbly gravel.

The Big River Trail was an assortment of trails, roads and turns, one of which I slipped in gravel and came down hard on my side. Two miles from the end of the ride — but better than two miles at the start of the ride, as Josh at the bike shop pointed out.

The bike lane across the Mississippi River is on a converted railroad bridge, fenced in with very few people on it the day we came across.

Despite the flat tire, the rain and my fall, we made it across Arkansas. When the woman at the bike shop, which is shipping my bike back to Seattle, heard about our journey, she said: “It was an eventful ride.”

And we ended it all with a ride in a pink Cadillac limo to a dinner with Elvis at the Marlowe Restaurant (order the ribs).

Dear Nile and Colorado rivers, don’t stop giving

Every article or book I have read about Egypt includes this quote from Herodotus (circa 490 — 425 BC): “Egypt is a gift of the Nile.”

So there. I have included it, too.

But I wonder if the Nile River might some day take back that gift or stop giving. Especially as Egypt and the 10 other countries that the Nile runs through “mistreat” the river.

Earliest traces of humans in Egypt go back 250,000 years, but the Nile’s gift started long after that when the climate changed and most of Egypt became a desert. Only place left to live was along the Nile. Today, 99 percent of 109 million Egyptians live on five percent of the land — along the Nile, according to a talk given to our tour group by Hany Hamroush. He has a doctorate in geochemistry from the University of Virginia, and returned to Egypt to teach at Cairo University and the American University in Cairo (AUC). His main research is on the impacts of the Nile River and the environmental changes in Egypt now and in the past.

The Nile gave Egypt river currents that flow south to north to float ships down the river and predominant winds that blow north to south to sail up the river. Trade, communications and finally a nation, a civilization. The Nile in Egypt comes from the White Nile, which starts in Lake Victoria in Uganda, and the Blue Nile, beginning in Ethiopia. Eighty-five percent of the runoff in Egypt comes from the Blue Nile, which brings with it lots of mud. Every year around June, the Nile floods in Egypt, bringing rich soil to plant crops in, water to irrigate them.

Until Jan. 15, 1971, when President Gamal Abdel Nasser opened the High Dam at Aswan.

The dam rises 366 feet above the river, is two and a quarter miles long, a half mile wide at its base with a road on top. No more silt from the Blue Nile, but many more megawatts of hydro power. As Toby Wilkinson puts it in his book “The Nile: A Journey Downriver Through Egypt’s Past and Present”:

“The High Dam has regulated the flow of the Nile, consigning the annual inundation — the natural phenomenon that built Egypt — to the history books.”

I could find no one who thought the High Dam was all good or all bad — and I admit I did very few man-on-the-street interviews while in Arabic-speaking Egypt. But in the reading I have done and the few people I talked to in Egypt, the consensus was “some good and some bad.”

Good because the dam brought about “medium floods,” as Hamroush put it. No more famines with low inundations. No more catastrophic floods like the one in 1927. The flood in 2021 was worse than the one in 1927 but not felt in Egypt because of the High Dam, said Hamroush. The dam produces about half of the electricity used in Egypt. Lake Nasser, the 300-mile-long waterway behind the High Dam, now has a productive fishery. The High Dam opened more land with year-round irrigation for agriculture.

Bad because the rich silt stops behind the High Dam. So chemical fertilizers must be used so that the country’s agriculture can feed the nation.

With the higher dam, more land cultivated, chemical fertilizers and more irrigation (think of the Nile as the only water source in Egypt — no rain, no snow pack inside the country), it sounds like agribusiness in the making. However, I looked for but only saw two tractors while in Egypt. Lots of donkeys, horses and manual labor. If Egypt can grow enough food by hand, more power to them.

More bad: Hamroush also pointed out that while silt is stuck behind the High Dam, there is less flow in the Nile so that any silt that reaches the Nile Delta doesn’t completely wash into the Mediterranean Sea. So the delta is sinking, and because of climate change, the sea is rising. The natural geological subsidence of the delta is 6.6 millimeters per year; the global sea rise is 3.3 millimeters per year. Doesn’t sound like much, but in 50 years it could affect four to eight million people, says Hamroush.

With more constant irrigation (mostly for sugar cane) there is more water damage to the foundations of ancient structures. Archeologist Kent Weeks discusses that in this video.

As Wilkerson puts it in his book: “The confident assertions of the High Dam’s cheerleaders, back in the late 1950s, now have a hollow ring. As one son of Aswan laconically put it, the High Dam ‘is slowly killing Egypt.’ “

And that’s not all. The Egyptians may now be paying more attention to how the Nile is treated, especially since someone else is doing the treating. Ethiopia has built and has filled the lake behind the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile. The concrete dam rises 475 feet above the river. The lake behind it covers 724 square miles (about the size of Houston, Texas). It will double Ethiopia’s output of electricity. Sounds good for Ethiopia, bad for Egypt.

For Egyptians, this could lead to ontological security—or the preservation of state identity. As this Carnegie article says:

“Ontological insecurity may arise when internal and external developments disrupt the continuity of established identities and worldviews. It could be argued, then, that the GERD project threatens the continuity of Egypt’s enacted world that sees the Nile as a living being inseparable from Egypt’s history, culture, and civilizational identity. Thus, developments related to the project could force Egypt to redefine its national identity that is centered on the Nile River.”

(Here’s another good article from the Brookings Institute.)

So the Nile could be caught between two huge dams, the High Dam in Egypt and the GERD in Ethiopia, sort of like the Colorado River in the United States, caught between Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams among others. Recently, the U.S. federal government came out with three options for how to use the water from the dwindling Colorado River, which could mean cutting off water to 10 million Americans or plugging the irrigation canals that support a “$4 billion industry that employs tens of thousands of people and puts vegetables in supermarkets across the country during the winter.”

Maybe the question more germane to the United States should be: What if the Colorado River stopped giving?

1 father, 100 children, how many mothers?

Ramses II had more than 100 children, and he probably had more than one wife. Maybe a harem or a concubine or two — or three or more. But he had one favorite wife, named Nefertari, and he built her a temple right beside his. Much smaller than his temple at Abu Simbel but more than the other mothers got.

Abu Simbel is on Lake Nasser, an artificial lake formed after the building of the High Dam at Aswan. Abu Simbel is about 700 miles south of Cairo, Egypt, and we flew and bused to visit. However, we visited other sites before leaving for Aswan and Abu Simbel. At Dahshur, we received a lesson in early pyramid building from a re-engineered pyramid that would collapse on itself if the angle of the sides were not changed, then to a “step” pyramid, think of smaller boxes stacked on top of each other. The Step Pyramid of King Djoser is considered the oldest stone structure on Earth, built more than 4,700 years ago. My favorite part came inside the tomb of Kagemni, a government official for King Teti (circa 2330 BC), where Eman, our guide, gave us our first lesson in hieroglyphics. The bas-relief carvings on the walls of the tomb show scenes from daily life.

But let’s get back to Abu Simbel. Pictured below is the Nefertari structure, at night during the light show and below that on our daytime visit. Known as the Temple of Hathor, a god usually depicted as a cow or woman, goddess of love, pleasure, patron of dancing and music. The six 30-foot statues show Ramses and Nefertari, her dressed as Hathor and the same height as Ramses’ statue. “Instead of knee-height, as most consorts were depicted,” according to Lonely Planet’s Egypt guidebook. Told you she was a fav.

At the upper far left (above) are carvings of baboons, active at sunrise and therefore greeting the sun and the sun god — something good to have on your temple. Ra-Horakhty stands between the broken statue of Ramses (down since ancient times) and the intact one. Nice to have gods on your temple as well. The temple was carved out of the mountain between 1274 and 1244 BC. Supposedly dedicated to gods Ra-Horakhty, Amun and Ptah, but Ramses shows up more than they do. With four statues more than 60 feet tall of himself, Ramses stared out over the Nile as a warning to any troublemaker who thought they would venture into his land.

If it’s Ramses’ temple, there have to be prisoners. Note the tied prisoners (above) who have different hair styles, representing that Ramses had conquests to the south, Nubia, and farther into the east of the Mediterranean Sea.

Let’s talk about those shining in the light. Kathy is always lit, but the rest of those in the sanctuary only light up twice a year, and Ptah, on the far right, never shines except when modern electric lights are on. As Ramses designed and built this structure, the first sunlight on February 21 and October 21 would shine far back in the temple to illuminate Ramses and two of the gods. But the sunlight stopped before falling on Ptah, a god of darkness. The special days were Ramses’ birthday and coronation days.

The structures at Abu Simbel represent two marvels, one in ancient times and another in more modern times. First marvel, that people more than 3,000 years ago with no power tools or bulldozers carved this out of the mountain in a way to make the sun shine where they wanted it to. Second marvel, that it was cut apart and moved more than 200 feet higher on the mountain when the High Dam at Aswan was built. The dam opened in 1971, and by then a venture headed up by UNESCO had lifted 35 temples, moving them above the rising lake waters. And the sun still shines. But now it falls on Ramses and two gods a day later.

If I haven’t yet endorsed Road Scholar, the group we toured with, let me do so now — just for the way they let us see Abu Simbel. A wander around in daylight, with Eman’s full explanation of it, the nighttime light show and then the early morning sail-by (video below) as we started sailing across Lake Nasser. Can’t say enough.

More on the High Dam in later posts.

Ramses II is not the only thing in the museum

Ramses II is an egotistical pharaoh, as our tour guide Eman pointed out, a ruler who might think his statue the most important of the more than 500,000 exhibits in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum. But that can’t happen here. We will let Ramses the Great lead us through our continuing Egyptian journey. But ignoring what else is in the museum could be seen as bowing down to Ramses. That’s something we don’t want to do since so many people who did never got back up.

The museum offers much more — more than you can see in a day, week or years. There’s the room set aside for items found in King Tutankhamun’s tomb, discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 (photography prohibited in that room). But Tut’s chair/throne is open for viewing (see below). More statues of other pharaohs and ancient Egyptian gods. Mummies, of course, and my favorite: The 52-foot long papyrus scroll of the Book of the Dead, the instructions a dead person needs to get to his second life. The scroll shows my slavery to the printed page, but the images from the more than 2,000-year-old document are as clear as something that came off my printer seconds ago. I could not get far enough away or have a wide enough lens to take in the whole scroll displayed on a museum wall. But here are photos of illustrations and the hieroglyphics:

Below are King Tut’s throne made of wood covered with gold and silver, ornamented with semi precious stones and colored glass. Lions’ heads protect the seat while the arms take the form of winged serpents wearing the double crown of Egypt (Lower and Upper) and guarding the names of the king. Found in Tut’s tomb in 1922.

The most famous bust of Nefertiti (1370 – c. 1330 BC) has been hauled off to Berlin, but the Cairo museum has several representations of the royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten, Tut’s father.

This statue of King Khafre (2558 – 2532 BC), below, was found at Giza, where the Great Pyramid sits. The second largest pyramid there was built by Khafre. The falcon god Horus sits behind Khafre’s head, providing protection and uniting earthly king with god.

Below is King Djoser (2667 – 2648 BC) who was buried in Egypt’s first pyramid, the world’s oldest monumental stone building.

Hatshepsut (1473 – 1458 BC), Egypt’s most famous ancient queen. What about Cleopatra? She brought the Egyptian rule to an end; Hatshepsut kept it alive during her 20-year reign and built several temples. Note the beard. She portrayed herself in statues and paintings with a male body and false beard.