Now that it is 2023, it’s time to catch up on the travels of 2022. Let’s go back to October and the last of three museums we visited in Washington, D.C.: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The path through the museum starts in Africa and takes the visitor through . . . actually, I’m not sure where it ends because we read, viewed and absorbed so much along the way that the museum keepers had to chase us out the exit doors – without even a visit to the bookstore or the gift shop. We made it past the civil-rights era of the 1960s and somewhat beyond.

I mostly got stuck in Africa and the early years of slavery in American colonies. Took me forever to stop reading about Queen Nzingha, who “had fought against (Portuguese) colonial and slave raiding attacks for decades.” She “died on December 17, 1663 at the age of 80. Unfortunately, her death accelerated Portuguese colonial occupation, as well as their Atlantic slave trade activities in central west Africa.”

Or, the slave trader Henry Laurens, who wrote to his son that he hated slavery while becoming rich from it. Now that I have been introduced to former slave Olaudah Equiano, I’d like to read his autobiography. I’d also like to read more about the 1808 law that prohibited importation of enslaved people to the United States but was a boon to the domestic slave trade as those slave already here and their progeny became more valuable.

I was especially stuck on the narrative laid out in this video, which I returned to twice (people love it when you go backwards through a crowd going forward through a museum):

Essentially, it says that when Africans arrived in the colonies, all of which held enslaved people, the system of slavery was not laid out. There were parts of the country where workers — Native Americans, European indentured servants and slaves – “labored, lived and rebelled together.” So new laws “defined who was enslaved and who was free. By 1750 the system of slavery was racialized and had become more uniform . . . The law based slavery on African descent and made it hereditary and lifelong. It took indentured servants out of slavery; it created whiteness.” (my italics)

“It created whiteness.” That seemed an odd thing to me, something that did not need to be created. White is white, it’s a color, and anyone who can see has some vision of what white is and how it differs from other colors. On further thought, it seemed that those who brought slavery to this neck of the woods should have sorted out who would be slave and who would not be. You might have thought they’d have this all figured out before spending the time and money to round up thousands of people in Africa, send them across the Atlantic and expect them to do all the work. But no. Previous efforts at assembling labor hadn’t worked out very well: Native Americans kept dying from the diseases Europeans spread to them; the problem with indentured servants was that they were indentured, they left when their term was up. But Africans, who seemed to survive longer than your local Indians and had less voice in things than indentured servants did? That’s what makes way for “racializing” slavery. Make slavery hereditary and forever. If you’re a slave, so are your children, their children and so on.

And, give whites the privilege to get out of it. Best to create a new societal term for what “white” means: a segment of society that is exempt from slavery, from chains, whipping, sold away from your family, endless toil picking cotton to sell to England textile makers to build a strong, rich country in a place that used to be a land sparsely populated by people who had their own way of living.

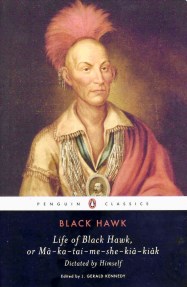

One of them, Chief Black Hawk, had an answer to all this. I said in previous posts that museums we visited in October overlap, and this spillover comes from the National Museum of the American Indian, or at least from a book I bought there, “Black Hawk: Life of Black Hawk or Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, dictated by Himself.”

Black Hawk was put in ball and chains, then dragged around the country and humiliated after he was captured while trying to protect his village and cornfields from the whites, defined above, who thought they had more right to them than the people who had lived there for hundreds of years. As he was paraded around the East Coast, his opinions were asked on many subjects, including what to do about the negroes, as he called them. He had a plan, which he hoped would be adopted:

“Let the free states remove all the male negroes (his italics) within their limits, to the slave states – then let our Great Father buy all the female negroes in the slave states, between the ages of twelve and twenty, and sell them to the people of the free states, for a term of years – say, those under fifteen until they are twenty-one – and those of, and over fifteen, for five years – and continue to buy all the females in the slave states, as soon as they arrive at the age of twelve, and take them to the free states, and dispose of them in the same way as the first – and it will not be long before the country is clear of black skins, about which, I am told, they have been talking, for a long time, and for which they have expended a large amount of money.”

His plan would clear the country of white skins, too, no matter the definition. He’d be called a pedophile today and put back in chains for sex trafficking. What he proposed seems impossible, maybe naive. But Black Hawk did not think this was beyond the capacity of whites. After all, they had dragged all these Africans to America and were in the process of removing all the Indian tribes from east of the Mississippi to the west of that river. If whites could do all that, why not turn everybody brown, much like me, said Chief Black Hawk.